- Introduction

- HTML5

- plotly Graphics

- plotly Charts

- plotly Maps

- Dash

- Callbacks

- Publishing

Introduction

This module will introduce you to Dash, a framework that integrates

Python, plotly, and Flask to

construct web-based dashboard in Python. We will work through a number

of simple examples of loading data, visualizing it with Python's built-in

graphics operations, then integrating those visualizations into an

interactive Dash web dashboard, which can be viewed online by anyone

with a web browser.

In order to fully understand how to use Dash, you need to also

understand

basic HTML5, plotly, and Python. HTML5 is used to define

the layout of the elements in your dashboard. plotly is used to

construct graphical components (visualizations) within your dashboard.

Finally, Python ties everything together to control used interaction

and changes on the dashboard based on the user's interaction

choices.

Setup

In order to use the Dash examples in this tutorial, you will need

to add the dash Python package. To do this, run the

Anaconda Prompt as an administrator, and at the command line enter the

following.

(base) C:> conda install -c conda-forge dash

HTML5

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is used to create

the layout (sections, paragraphs, headings, links, and so on) for web

pages and web applications. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee developed the

concept for HTML while working in the computer services section of

CERN, the European Laboratory for Particle Physics in

Geneva. Berners-Lee suggested that, rather than downloading research

documents as files from individual computers, you could

instead link to the text of the files themselves. This would

form a cross-reference system between research documents. From one

research paper, you could display the content of another paper that

held relevant text or diagrams. The cross-reference system could be

seen as a web of information held across computers throughout

the world.

Berners-Lee's idea was followed by Hypercard, a filing-card

type application for the Apple Macintosh built by Bill Atkinson. The

main limitation of this system was that hypertext jumps could

only be made on files held on the same computer. In the mid 90s, the

Internet developed the Domain Name System (DNS) that mapped

easy-to-remember names like www.ncsu.edu to their

corresponding IP addresses, a unique locator for a given

domain. Berners-Lee built on this to develop the HyperText Transfer

Protocol (HTTP) and the HyperText Markup Language (HTML), defining a

method to transmit HTML documents between computers using HTTP.

Up to this point, HTML was mostly a research-centered idea. In

1992, the National Center for Supercomputer Applications (NCSA) at the

University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign (UIUC) developed the first web

browser, Mosaic. Mosaic was released on Sun Microsystems

workstations in 1993. This was followed by Netscape in 1994, built by

Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark. Next came Internet Explorer in 1995,

Google Chrome in 1998, and the Mozilla foundation (the precursor to

Firefox) in 2003.

It is beyond the scope of our module to discuss all aspects of

HTML, and for Dash, it is not required, since all we're concerned

about is how different HTML tags affect the layout of

information. To this end, we list below some of the common HTML tags

important to Dash and their corresponding

purpose. A complete list of

tags is available online.

- •

div - A section of a document

- •

H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6 - Headers

in decreasing priority

- •

p - A paragraph

- •

span - A block of text, usually with

properties different from the surrounding text

- •

br - A line break

- •

ol - An ordered list

- •

ul - An unordered list

- •

li - A list item in an ordered or

unordered list

- •

input - An input component, where

the type of input is defined by the

input's

type attribute: input box,

checkboxes, radiobuttons, and so on.

- •

table - A table

- •

tbody - Definition of where a

table's body starts and stops

- •

tr - A single table row

- •

td - A single table column value

(embedded within a table row defined

with

<tr>)

- •

thead - Definition of where a

table's header starts and stops

- •

th - A single table column value

in the table's header (embedded within a table row defined

with

<tr>)

- •

tfoot - Definition of where a

table's footer starts and stops

- •

tf - A single table column value

in the table's footer (embedded within a table row defined

with

<tr>)

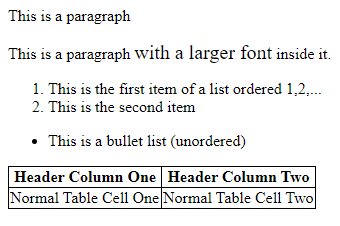

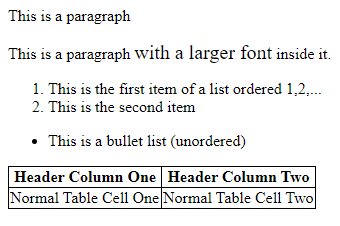

Here is a very simple web page demonstrating some of these tags in

use.

<html>

<body>

<div>

<p>This is a paragraph</p>

<p>This is a paragraph <span style='font-size: 1.25em'>with a larger font</span> inside it.</p>

<ol>

<li>This is the first item of a list ordered 1,2,...</li>

<li>This is the second item</li>

</ol>

<ul>

<li>This is a bullet list (unordered)</li>

</ul>

<table style='border-collapse: collapse;'>

<tr>

<th style='border: 1px solid black;'>Header Column One</th>

<th style='border: 1px solid black;'>Header Column Two</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style='border: 1px solid black;'>Normal Table Cell One</td>

<td style='border: 1px solid black;'>Normal Table Cell Two</td>

</tr>

</table>

</div>

</body>

</html>

The result of executing the HTML code in a web browser

The result of executing the HTML code in a web browser

plotly

plotly is a Python library designed to provide a wide

range of standard charts. plotly is built on the Plotly JavaScript

library, and is meant to support creation of interactive web-based

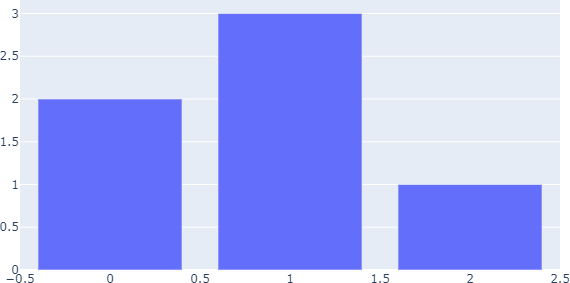

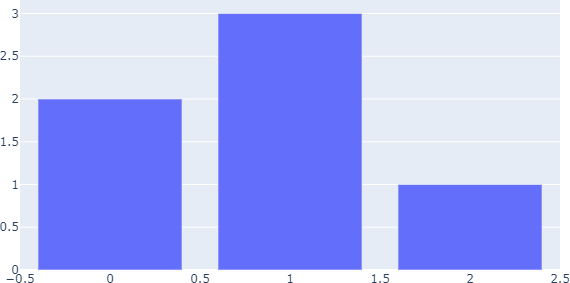

visualizations. As an example, here is a plotly program that can be

run in a Jupyter notebook.

% import plotly.graph_objects as go

%

% fig = go.Figure( data=go.Bar( y=[2,3,1] ) )

% fig.show()

This produces the following simple bar chart.

A

A plotly bar chart

Charts

Although plotly can be used directly to create charts, it is

generally recommended to start with Plotly Express, which sits

on top of plotly and allows entire figures to be created in a more

efficient fashion. Plotly Express functions use plotly graph objects

internally and return a plotly.graph_object.figure

instance. plotly's documentation shows examples of how to build a

graph in Plotly Express, followed by code to build the equivalent

graph in plotly. Since Plotly Express returns a basic plotly figure

instance, modifications of the Plotly Express charts can be done in

way that is identical to how plotly's charts are changed. We will use

Plotly Express code whenever it is possible.

To provide you with examples of how to build the basic charts and

graphs you will want to use in your dashboards, we provide a

collection of code and resulting graphs that Plotly Express

supports.

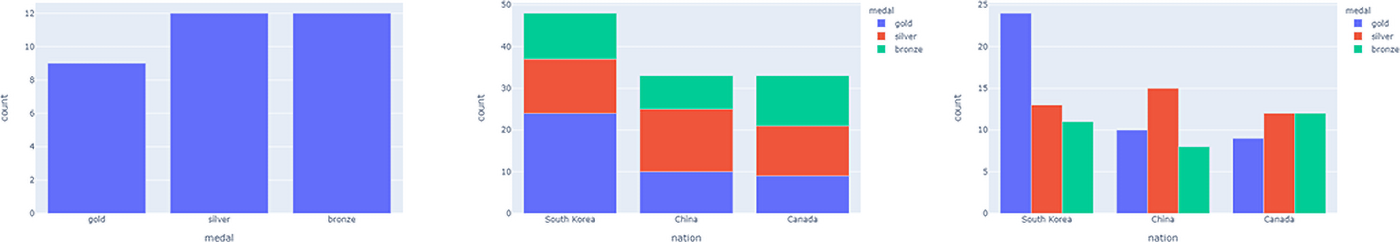

Bar Graph

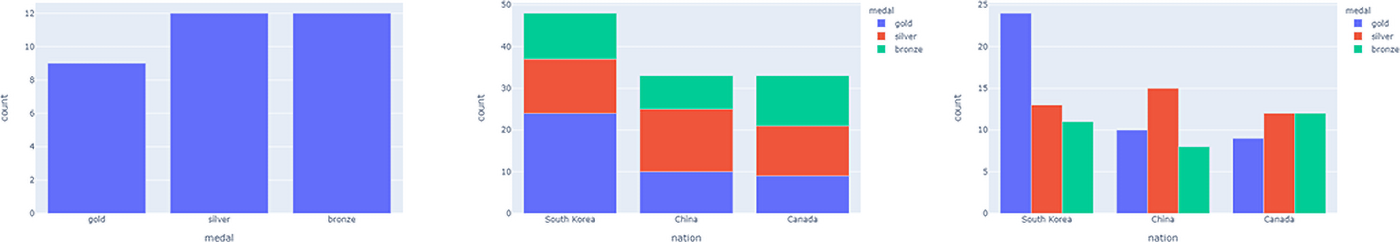

Plotly Express supports bar charts, stacked bar charts, and

side-by-side bar charts.

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% df = px.data.medals_long()

%

% canada = df[ df[ 'nation' ] == 'Canada' ]

% fig = px.bar( canada, x='medal', y='count' )

% fig.show()

%

% fig = px.bar( df, x='nation', y='count', color='medal' )

% fig.show()

%

% fig = px.bar( df, x='nation', y='count', color='medal', barmode='group' )

% fig.show()

A

A plotly bar chart, stacked bar chart, and

side-by-side bar chart

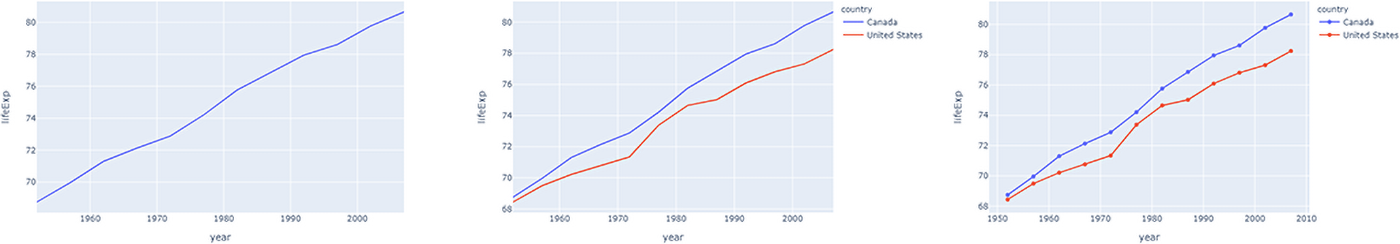

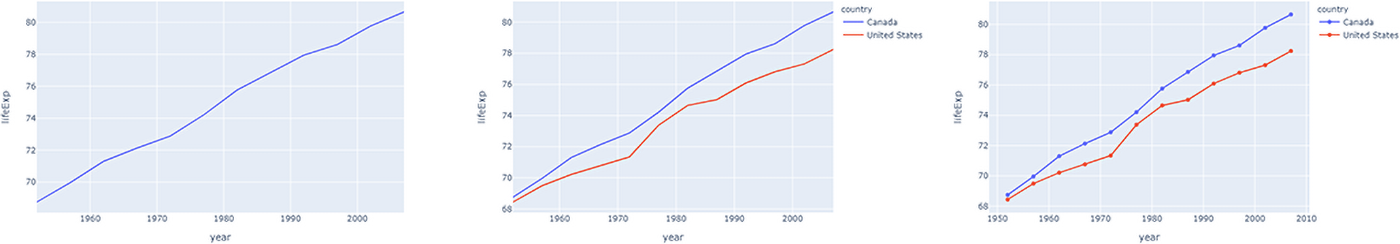

Line Graph

Plotly Express supports line graphs with one or more lines.

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% canada = px.data.gapminder().query( 'country=="Canada"' )

% US = px.data.gapminder().query( 'country=="United States"' )

%

% fig = px.line( canada, x='year', y='lifeExp' )

% fig.show()

%

% df = pd.concat( [ canada, US ] )

% fig = px.line( df, x='year', y='lifeExp', color='country' )

% fig.show()

%

% fig.update_traces( mode='markers+lines' )

% fig.show()

A

A plotly single trace line chart, double

trace line chart, and double trace line chart with markers at each

sample point bar chart

Notice the command

fig.update_traces( 'markers+lines' ) that adds

markers to the traces at each sample point, in addition to the

default connected lines. This is an example of a plotly command used

to augment a figure returned from Plotly Express. You might wonder

what a "trace" is. From the plotly documentation, "a trace is just the

name we give a collection of data and the specifications of which we

want that data to be plotted." In other words, a trace is a

visualization, or a component of a visualization. If you're curious,

the same two-trace line chart with markers would be created in plotly

as follows.

% import plotly.express as px

% import plotly.graph_objects as go

% import pandas as pd

%

% canada = px.data.gapminder().query( 'country=="Canada"' )

% US = px.data.gapminder().query( 'country=="United States"' )

%

% fig = go.Figure()

% fig.add_trace( go.Scatter( x=canada[ 'year' ], y=canada[ 'lifeExp' ], mode='markers+lines', name='Canada' ) )

% fig.add_trace( go.Scatter( x=US[ 'year' ], y=US[ 'lifeExp' ], mode='markers+lines', name='United States' ) )

%

% fig.show()

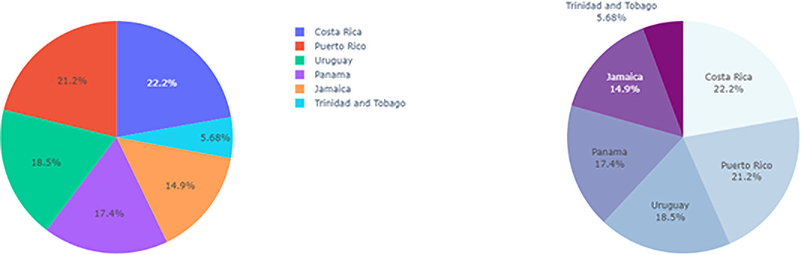

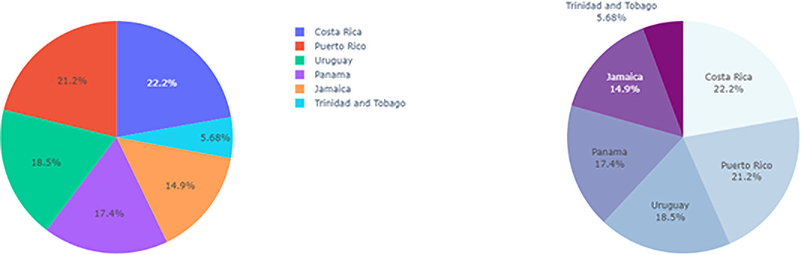

Pie Chart

Plotly Express supports standard line charts.

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% df = px.data.gapminder().query( 'year==2007' ).query( 'continent=="Americas"' )

% df_small = df[ df[ 'pop' ] < 5000000 ]

%

% fig = px.pie( df_small, values='pop', names='country' )

% fig.show()

A

A plotly pie charts, default and augmented

with update_traces

The pie chart can be improved using fig.update_traces,

for example, to order slices largest-to-smallest clockwise from the

top of the chart, and to change the colours to ones more appropriate

for a discrete six-value sequence.

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% df = px.data.gapminder().query( 'year==2007' ).query( 'continent=="Americas"' )

% df_small = df[ df[ 'pop' ] < 5000000 ]

%

% fig = px.pie( df_small, values='pop', names='country' )

%

% colours=[ '#edf8fb', '#8856a7', '#8c96c6', '#bfd3e6', '#810f7c', '#9ebcda' ]

% fig.update_traces( direction='clockwise', sort=True, marker_colors=colours, textinfo='label+percent', showlegend=False )

% fig.show()

Scatterplot

Plotly Express supports scatterplots, including linear and

non-linear locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS)

trendlines.

% import plotly.express as px

%

% fig = px.scatter( x=[0,1,2,3,4], y=[0,1,4,9,16] )

% fig.show()

%

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% df = px.data.iris()

%

% fig = px.scatter( df, x='sepal_width', y='sepal_length', color='species', size='petal_length', trendline='ols' )

% fig.show()

A

A plotly scatterplot, scatterplot with

ordinary least squares trend lines, and scatterplot with non-linear

cubic trend lines

More sophisticated non-linear trendlines (e.g., a cubic polynomial

fit) can be constructed and added using numpy and plotly.

% import plotly.express as px

% import plotly.graph_objects as go

% import numpy as np

% import pandas as pd

%

% def cubic_fit( df, type, prop_x, prop_y ):

% x = df[ df[ 'species' ] == type ][ prop_x ].to_numpy()

% y = df[ df[ 'species' ] == type ][ prop_y ].to_numpy()

% z = np.polyfit( x, y, 3 )

% f = np.poly1d( z )

%

% x_fit = np.linspace( x.min(), x.max(), 100 )

% y_fit = f( x_fit )

% return (x_fit,y_fit)

%

% df = px.data.iris()

% fig = px.scatter( df, x='sepal_width', y='sepal_length', color='species', size='petal_length' )

%

% x_fit_setosa,y_fit_setosa = cubic_fit( df, 'setosa', 'sepal_width', 'sepal_length' )

% x_fit_versicolor,y_fit_versicolor = cubic_fit( df, 'versicolor', 'sepal_width', 'sepal_length' )

% x_fit_virginica,y_fit_virginica = cubic_fit( df, 'virginica', 'sepal_width', 'sepal_length' )

%

% fig.add_trace( go.Scatter( x=x_fit_setosa, y=y_fit_setosa, name='Setosa Fit', marker=go.Marker( color='rgb(100,100,255)' ) ) )

% fig.add_trace( go.Scatter( x=x_fit_versicolor, y=y_fit_versicolor, name='Versicolor Fit', marker=go.Marker( color='rgb(255,100,100)' ) ) )

% fig.add_trace( go.Scatter( x=x_fit_virginica, y=y_fit_virginica, name='Virginica Fit', marker=go.Marker( color='rgb(100,200,100)' ) ) )

% fig.show()

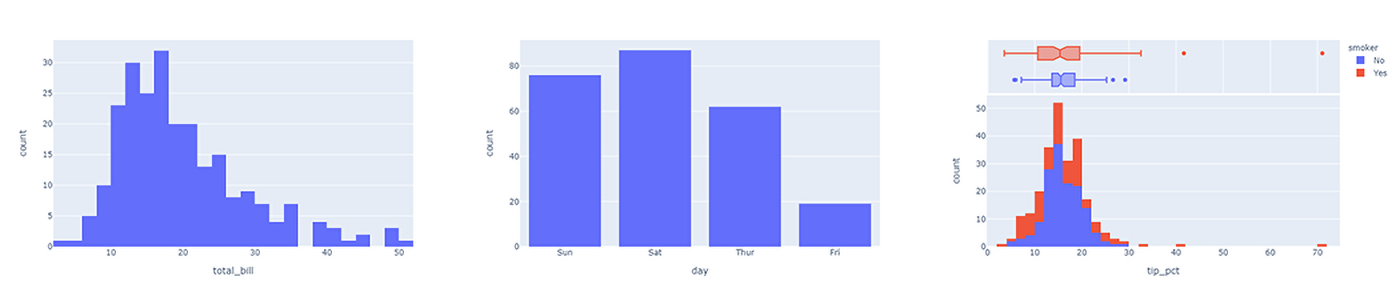

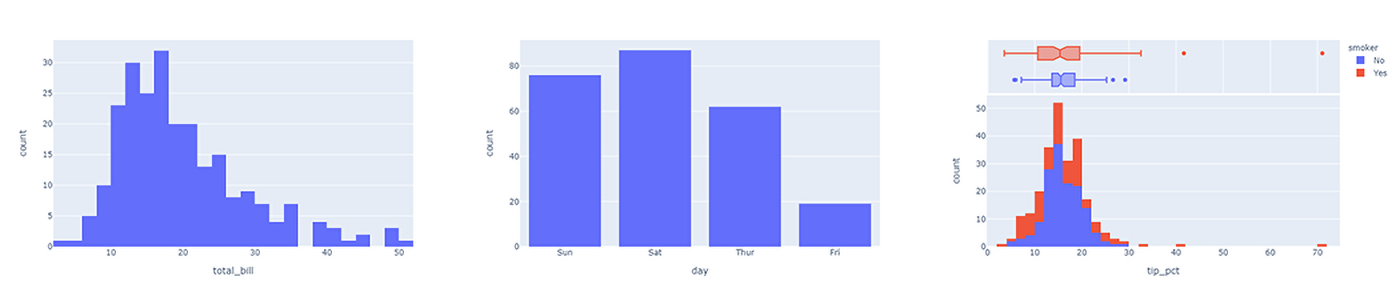

Histogram

Plotly Express supports histograms for both continuous and

categorical (discrete) data.

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% df = px.data.tips()

% fig = px.histogram( df, x='total_bill' )

% fig.show()

%

% fig = px.histogram( df, x='day' )

% fig.show()

%

% df[ 'tip_pct' ] = df[ 'tip' ] / df[ 'total_bill' ] * 100.0

% fig = px.histogram( df, x='tip_pct', color='smoker', marginal='box' )

% fig.show()

A

A plotly continuous data histogram, categorical data

histogram, and continuous data histogram coloured by smoker, with

a boxplot by smoker shown as a marginal visualization above the

histogram

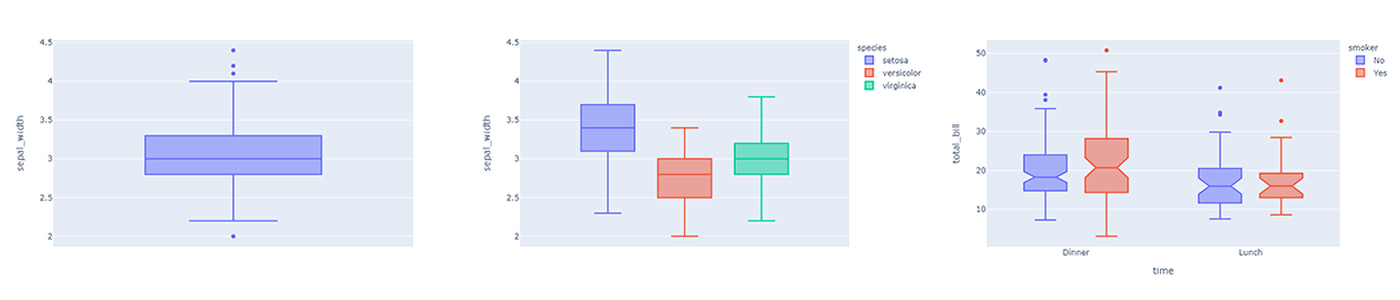

Boxplot

Plotly Express supports boxplots, including outlier visualization

and different methods of quartile computation.

% import plotly.express as px

%

% df = px.data.iris()

% fig = px.box( df, y='sepal_width' )

% fig.show()

%

% fig = px.box( df, y='sepal_width', color='species' )

% fig.show()

%

% df = px.data.tips()

% fig = px.box( df, x='time', y='total_bill', color='smoker', notched=True )

% fig.show()

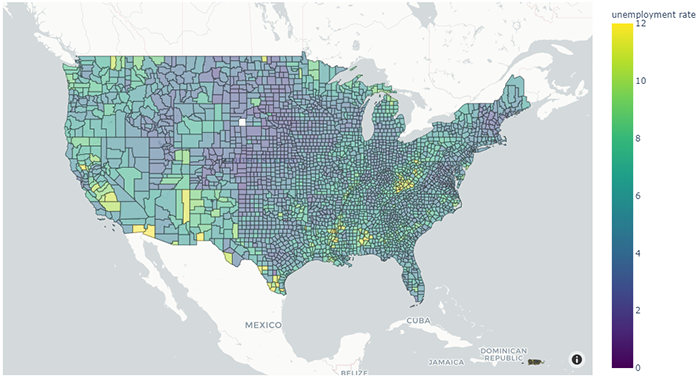

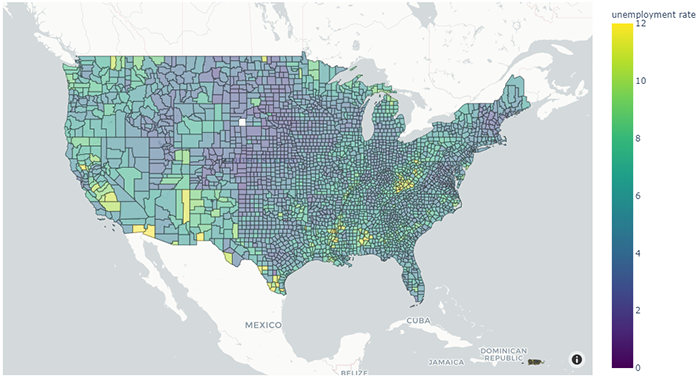

Maps

plotly supports maps using Mapbox, a map and location service for developers.

Some plotly maps may require a Mapbox account and public Mapbox

access token. Others do not. The documentation identifies when a

public token is needed.

To start, we show an example of a choropleth map visualizing

unemployment rate by continental US county. Choropleth maps require

two arguments.

- A GeoJSON-formatted geometry variable, where each geographic

feature has a specific ID field: the field identifier.

- A list of values to visualize, where each value has a specific

field identifier identical to the type used in the GeoJSON data.

The GeoJSON data is passed as a geojson argument, and

the data to visualize within the geography is passed as the

color argument of a px.choropleth_mapbox

object. The geography and value to visualize are mapped to one another

using the field identifier, which must exist in both the GeoJSON and

data structures. In our example, a county's Federal Information

Processing Standards (FIPS) code is used as the field identifier, and

exists in both the GeoJSON object and the unemployment data frame.

% import json

% import pandas as pd

% import plotly.express as px

% from urllib.request import urlopen

%

% with urlopen( 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plotly/datasets/master/geojson-counties-fips.json' ) as response:

% counties = json.load( response )

%

% df = pd.read_csv( 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plotly/datasets/master/fips-unemp-16.csv', dtype={ 'fips': str } )

%

% fig = px.choropleth_mapbox(

% df,

% geojson=counties,

% locations='fips',

% color='unemp',

% color_continuous_scale='Viridis',

% range_color=(0,12),

% mapbox_style='carto-positron',

% zoom=3,

% center={'lat': 37.0902, 'lon': -95.7129},

% opacity=0.5,

% labels={'unemp': 'unemployment rate' }

% )

% fig.update_layout( margin={ 'r': 0, 't': 0, 'l': 0, 'b': 0 } )

% fig.show()

A

A plotly choropleth map of unemployment by US country

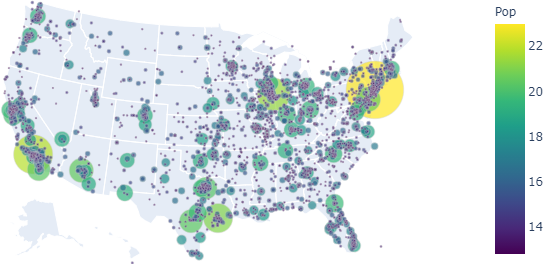

Mapbox maps do not support changing the map projection. To do this,

outline-based Geo maps must be used instead. A Geo

map's projection type can be changed with

fig.update_geos( projection_type='mercator' ). Numerous projects types are supported.

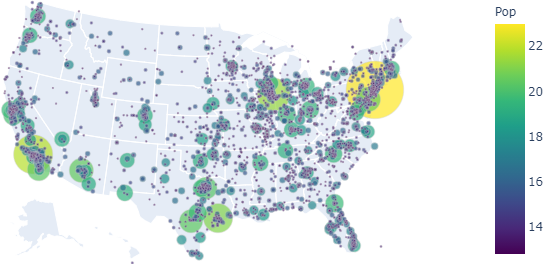

The example code below creates a population proportional dot map

for the United States using a Geo map created with the

go.Scattergeo plotly command.

% import plotly.graph_objects as go

% import numpy as np

% import pandas as pd

%

% df = pd.read_csv( 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plotly/datasets/master/2014_us_cities.csv' )

% scale = 5000

%

% fig = go.Figure()

%

% fig.add_trace( go.Scattergeo(

% lon=df[ 'lon' ],

% lat=df[ 'lat' ],

% marker = {

% 'size': df[ 'pop' ] / scale,

% 'colorscale': 'Viridis',

% 'color': np.log2( df[ 'pop' ] ),

% 'line_color': 'rgb(200,200,200)',

% 'line_width': 0.5,

% 'sizemode': 'area',

% 'colorbar': {

% 'title': 'Pop',

% 'titleside': 'top'

% }

% }

%

%

% fig.update_layout(

% geo = dict(

% showland=True,

% lataxis = dict( range=[ 18, 51 ] ),

% lonaxis = dict( range=[ -124, -66 ] ),

% countrycolor = 'rgb(217,217,217)',

% countrywidth = 0.5

% )

%

%

% fig.update_geos( projection_type='albers usa' )

%

% fig.show()

A

A plotly proportional dot map of city location and

population

Dash

Finally, we can start our discussion of Dash dashboards. As we

initially noted, Dash dashboards are made up of two parts:

a layout that defines how elements are position on a web page,

and interactivity that defines how users can manipulate

elements of the web page to change what it displays.

As a simple example, below is a Dash dashboard that displays

a side-by-side bar graph of the number of fruit associated with the

cities SF and Montreal. Dash dashboards

are normally run as stand-alone python code, and not within a Jupyter

notebook.

- Enter the Python code for the dashboard in an external file.

- Use

python to execute the file.

- By default, Dash places the dashboard

at http://127.0.0.1:8050/, which is shorthand for the

computer being used to access the address (i.e., your computer, or

localhost in technical terms) over port 8050. By visiting that

URL, you can view and interact with the dashboard defined in your

Python file.

% from dash import Dash

% from dash import html

% from dash import dcc

% from dash import Input

% from dash import Output

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% ext_SS = ['https://codepen.io/chriddyp/pen/bWLwgP.css']

% app = Dash(__name__, external_stylesheets=ext_SS)

%

% df = pd.DataFrame( {

% 'Fruit': ['Apples','Oranges','Bananas','Apples','Oranges','Bananas'],

% 'Amount': [4,1,2,2,4,5],

% 'City': ['SF','SF','SF','Montreal','Montreal','Montreal']

% } )

%

% fig = px.bar( df, x='Fruit', y='Amount', color='City', barmode='group' )

%

% app.layout = html.Div(

% children=[

% html.H1( children='Dash dashboard example' ),

% html.Div( children='Fruit Counts for SF and Montreal' ),

%

% dcc.Graph( id='ex_graph', figure=fig )

% ])

%

% app.run_server(debug=True)

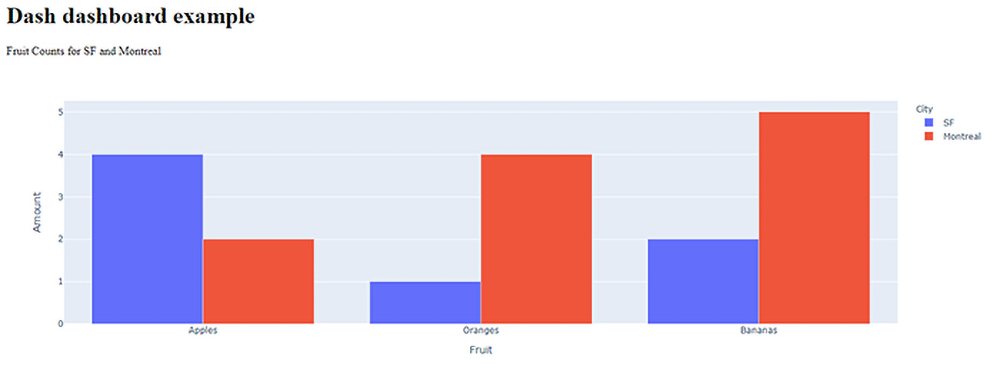

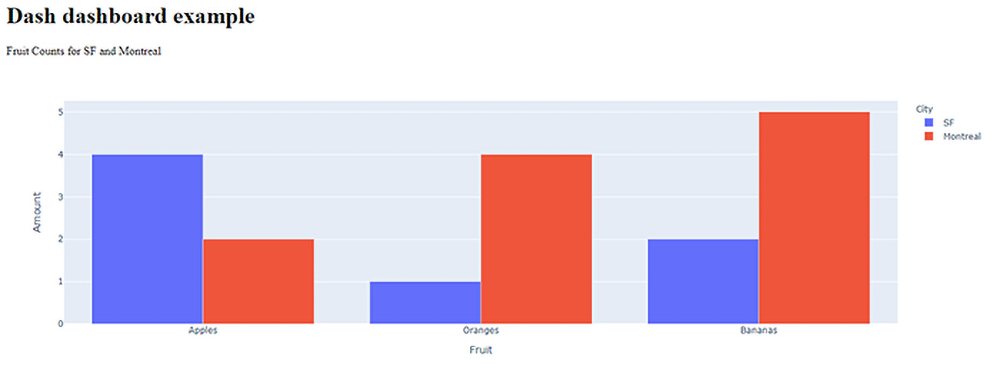

Running this code, then visiting URL http://127.0.0.1:8050 produces the following

(non-interactive) visualization in a web browser.

A Dash dashboard showing the number of three fruit for two different

cities, visualized as a side-by-side bar chart

A Dash dashboard showing the number of three fruit for two different

cities, visualized as a side-by-side bar chart

To end the dashboard, terminate the Python program running

dash-app.py. A very simple explanation of the components

of this program is as follows.

app = dash.Dash(… creates the initial

Dash application using the community-recommended styles loaded from

plotly,

df = pd.DataFrame… creates a pandas

dataframe with the data we will visualize,

fig = px.bar… creates a plotly bar

graph,

app.layout = html.Div(… defines the

dashboard's layout as an initial HTML div,

children=[… places an H1

section title, a div, and a graph element within the

parent div,

html.H1 and html.Div define the title

and subtitle of the dashboard,

dcc.Graph… displays the plotly bar

graph, and assigns it an ID of ex_graph, and

app.run_server(debug=True) interprets the code to

create the dashboard at URL http://127.0.0.1:8050/

One clarifying note about setting debug=True in the

run_server function: when debug is False, changes to the

Python code will not update the dashboard. When debug is True, changes

to the Python code will automatically be detected and used to update

the dashboard in real-time. If you are using debug=True

you can run your code (based on my testing) from an Anaconda Prompt or

the Spyder IDE. We DO NOT recommend running the code in a

Jupyter notebook. Although it will run correctly the first time, there

is no easy way to terminate the dashboard if you want to re-run

it.

Setting debug=True will also add a blue button

containing < > at the bottom-right of the

screen. Clicking on this button allows you to check the status of the

Dash server, view any errors that may have occurred, and visualize the

callback graph for the dashboard.

HTML objects have default styles that can be changed in

various ways. Dash supports this ability by providing access to a

tag's style properties through update_layout() for

figures and style for Dash layouts. The following code is

a modification of the original example.

% from dash import Dash

% from dash import html

% from dash import dcc

% from dash import Input

% from dash import Output

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% ext_SS = ['https://codepen.io/chriddyp/pen/bWLwgP.css']

% app = Dash(__name__, external_stylesheets=ext_SS)

% colours = { 'background': '#111111', 'text': '#7fdbff' }

%

% df = pd.DataFrame( {

% 'Fruit': ['Apples','Oranges','Bananas','Apples','Oranges','Bananas'],

% 'Amount': [4,1,2,2,4,5],

% 'City': ['SF','SF','SF','Montreal','Montreal','Montreal']

% } )

%

% fig = px.bar( df, x='Fruit', y='Amount', color='City', barmode='group' )

% fig.update_layout(

% plot_bgcolor=colours[ 'background' ],

% paper_bgcolor=colours[ 'background' ],

% font_color=colours[ 'text' ]

% )

%

% app.layout = html.Div(

% style={ 'backgroundColor': colours[ 'background' ] },

% children=[

% html.H1(

% children='Dash dashboard example',

% style={ 'textAlign': 'center', 'color': colours[ 'text' ] }

% ),

% html.Div(

% children='Fruit Counts for SF and Montreal',

% style={ 'textAlign': 'center', 'color': colours[ 'text' ] }

% ),

%

% dcc.Graph( id='ex_graph', figure=fig )

% ]

% )

%

% app.run_server(debug=True)

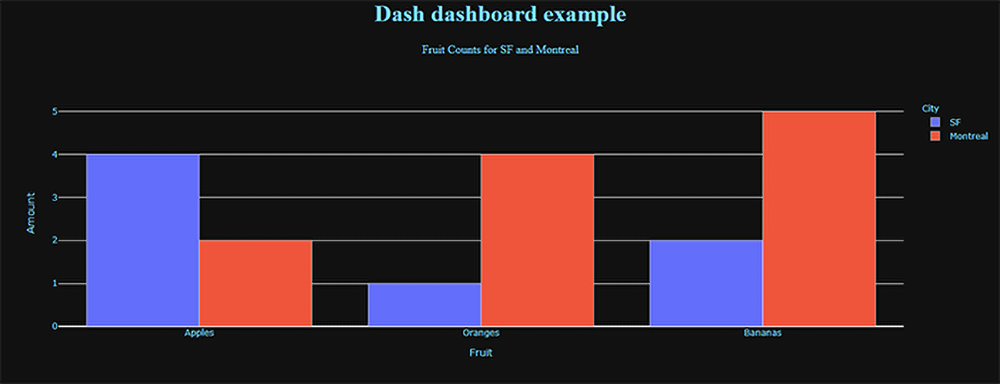

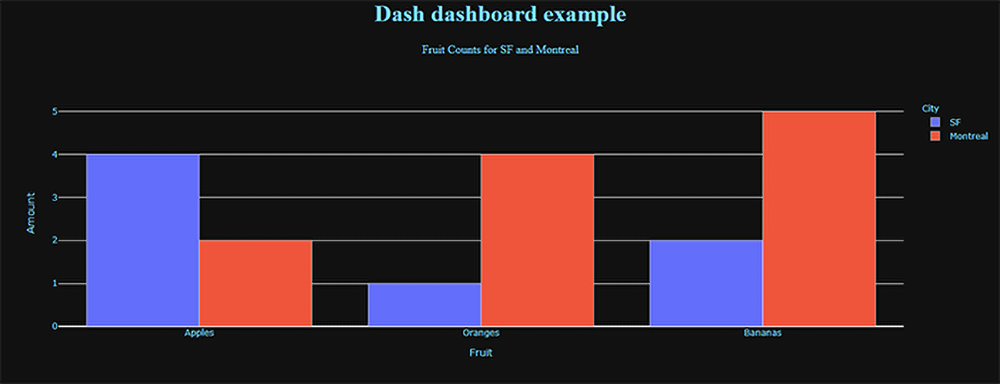

A Dash dashboard showing the number of three fruit for two different

cities, visualized as a side-by-side bar chart, with HTML styles

applied to control dashboard colours

A Dash dashboard showing the number of three fruit for two different

cities, visualized as a side-by-side bar chart, with HTML styles

applied to control dashboard colours

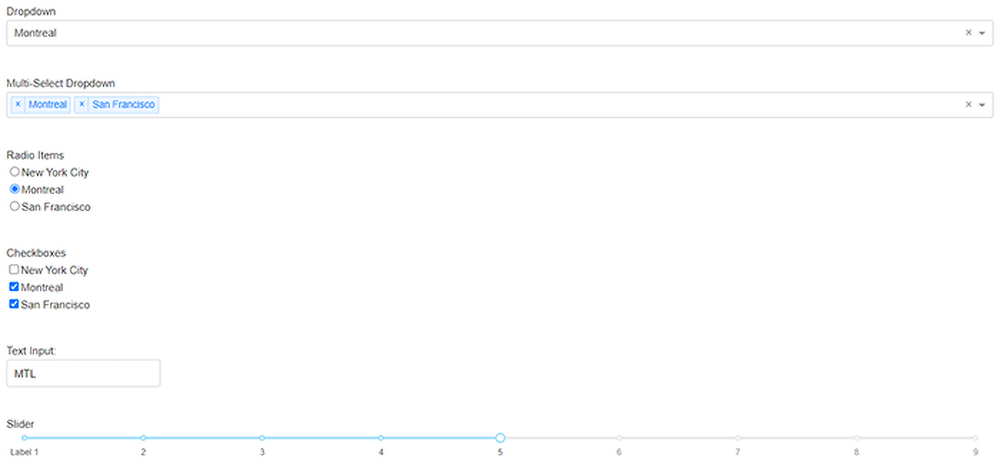

Interactive Widgets

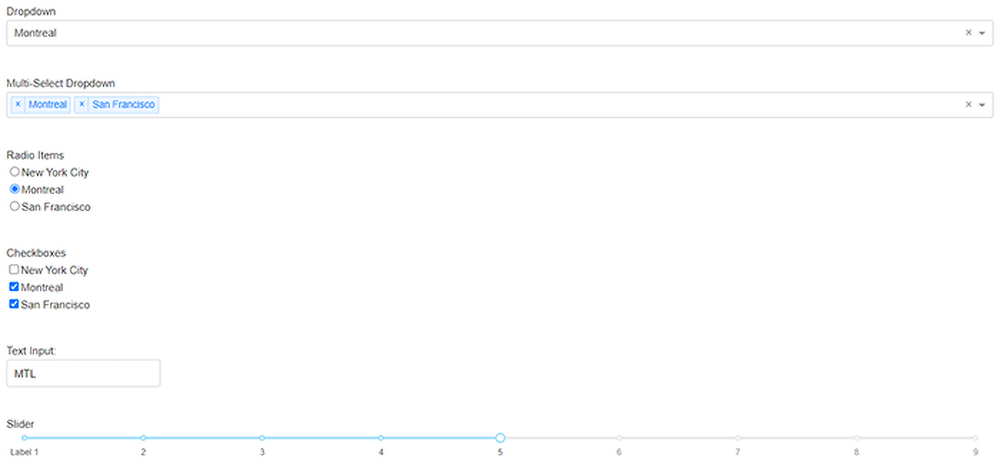

As with most applications, Dash provides a set of standard widgets

to allow users to interact with an application. The code below shows a

sample of Dash's interactive objects, including dropdown and

multi-dropdown menus, radiobuttons, checkboxes, input fields, and

sliders.

% from dash import Dash

% from dash import html

% from dash import dcc

% from dash import Input

% from dash import Output

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% ext_SS = ['https://codepen.io/chriddyp/pen/bWLwgP.css']

% app = Dash(__name__, external_stylesheets=ext_SS)

%

% app.layout = html.Div([

% html.Label('Dropdown'),

% dcc.Dropdown(

% options=[

% {'label': 'New York City', 'value': 'NYC'},

% {'label': 'Montreal', 'value': 'MTL'},

% {'label': 'San Francisco', 'value': 'SF'}

% ],

% value='MTL'

% ),

% html.Div(style={'padding': '20px'}),

%

% html.Label('Multi-Select Dropdown'),

% dcc.Dropdown(

% options=[

% {'label': 'New York City', 'value': 'NYC'},

% {'label': 'Montreal', 'value': 'MTL'},

% {'label': 'San Francisco', 'value': 'SF'}

% ],

% value=['MTL', 'SF'],

% multi=True

% ),

% html.Div(style={'padding': '20px'}),

%

% html.Label('Radio Items'),

% dcc.RadioItems(

% options=[

% {'label': 'New York City', 'value': 'NYC'},

% {'label': 'Montreal', 'value': 'MTL'},

% {'label': 'San Francisco', 'value': 'SF'}

% ],

% value='MTL'

% ),

% html.Div(style={'padding': '20px'}),

%

% html.Label('Checkboxes'),

% dcc.Checklist(

% options=[

% {'label': 'New York City', 'value': 'NYC'},

% {'label': 'Montreal', 'value': 'MTL'},

% {'label': 'San Francisco', 'value': 'SF'}

% ],

% value=['MTL', 'SF']

% ),

% html.Div(style={'padding': '20px'}),

%

% html.Label('Text Input: '),

% dcc.Input(value='MTL', type='text'),

% html.Div(style={'padding': '20px'}),

%

% html.Label('Slider'),

% dcc.Slider(

% min=1,

% max=9,

% marks={i: 'Label {}'.format(i) if i == 1 else str(i) for i in range(1, 10)},

% value=5,

% )

% ])

%

% app.run_server(debug=True)

Examples of Dash dropdown, multi-dropdown, radiobutton group,

checkbox group, text input, and slider widgets

Examples of Dash dropdown, multi-dropdown, radiobutton group,

checkbox group, text input, and slider widgets

Callbacks

Once interactive widgets are placed on a dashboard, we need a way

to recognize when they are changed. This is done

using callbacks, a standard method to monitor user interaction

in an application. Whenever a widget is manipulated to change its

value, a callback is made to the Python program controlling the

dashboard. Code in the program captures the callback, so it can

examine the new widget value and update the dashboard's content

appropriately.

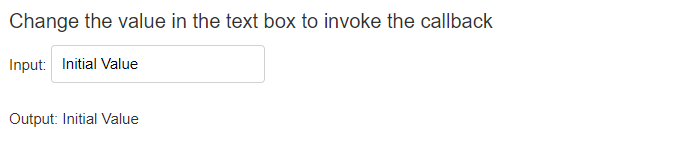

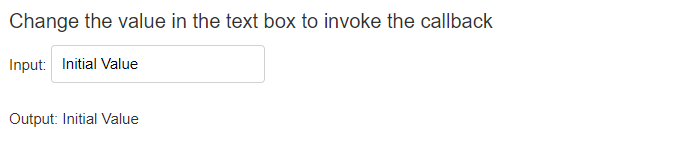

As a very simple example of callbacks, the following Python program

creates a Dash dashboard with an input text field, and an output label

that displays the current value of the text field.

% from dash import Dash

% from dash import html

% from dash import dcc

% from dash import Input

% from dash import Output

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% ext_SS = ['https://codepen.io/chriddyp/pen/bWLwgP.css']

% app = Dash(__name__, external_stylesheets=ext_SS)

%

% app.layout = html.Div( [

% html.H6( 'Change the value in the text box to invoke the callback' ),

% html.Div( [

% 'Input: ',

% dcc.Input( id='inp', value='Initial Value', type='text' )

% ] ),

% html.Br(),

% html.Div( id='out' )

% ] )

%

% @app.callback(

% [ Output(component_id='out', component_property='children') ],

% [ Input(component_id='inp', component_property='value') ],

% )

% def update_output_div( input_value ):

% s = 'Output: {}'.format( input_value )

% return [ s ]

%

% app.run_server(debug=True)

A Dash input textbox and a callback that displays the current value

of the textbox in a

A Dash input textbox and a callback that displays the current value

of the textbox in a div

We have already discussed the code used to create the dashboard and its

corresponding widgets. The @app.callback function is where

a callback to detect changes to the input textbox and modify the output

div is contained.

@app.callback defines the inputs

and outputs of the dashboard.

@app.callback is described as

a decorator in Dash. It tells Dash to call this function

whenever the value of an input changes, presumably in order to update

the children of an output.

Input defines the input component and the input's

property that contains a new input value. In our example, the input

component is the dcc.Input textbox with the

ID inp. The new input value is the value

property of the textbox.

Output defines the output recipient and the

recipient's property. In our example, the recipient is the component

in our layout with the ID out (a div). The

recipient's children value will be updated with the new

input value.

- Immediately following

@app.callback is a function

that takes the new input value as an argument, and returns a new

output value to store in the recipient's property. Note that the

function must be defined immediately after

the @app.callback function, with no blank lines or other

intervening code.

- The callback function can be named as desired, although it should

usually reflect the purpose of the callback. In our

code,

update_output_div takes input_value,

which is the new value of the textbox, and returns a string containing

this new value.

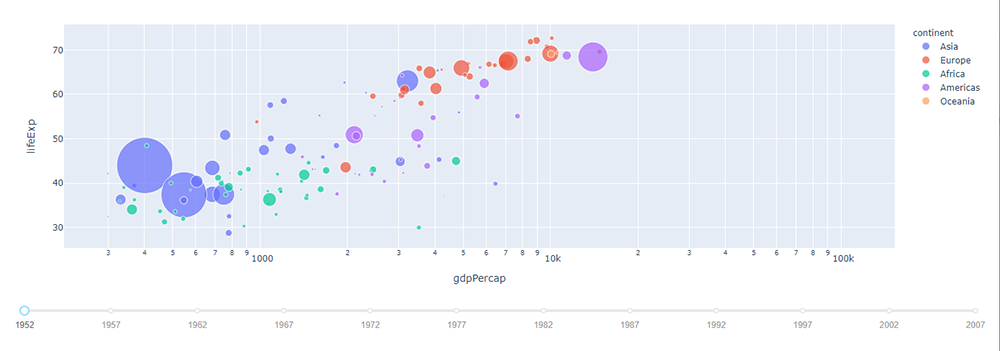

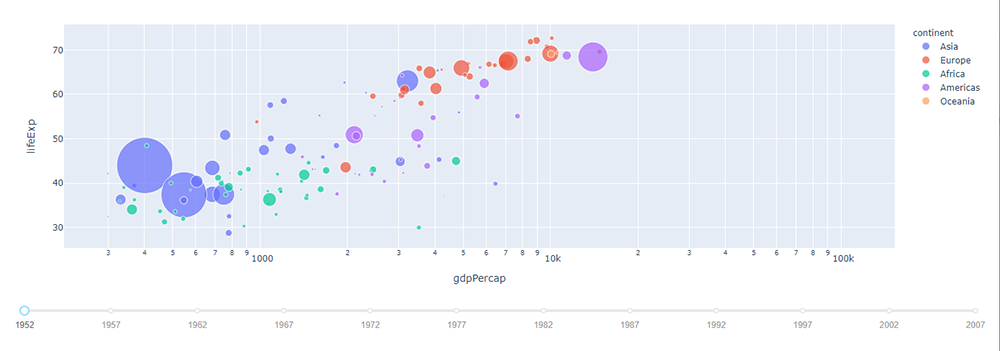

Here is another, more realistic, example that uses a slider and a

scatterplot to visualize the relationship between GDP per capita and

life expectancy, subdivided by continent.

% from dash import Dash

% from dash import html

% from dash import dcc

% from dash import Input

% from dash import Output

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% df = pd.read_csv( 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plotly/datasets/master/gapminderDataFiveYear.csv' )

%

% ext_SS = ['https://codepen.io/chriddyp/pen/bWLwgP.css']

% app = Dash(__name__, external_stylesheets=ext_SS)

%

% app.layout = html.Div( [

% dcc.Graph( id='graph-with-slider' ),

% dcc.Slider(

% id='year-slider',

% min=df['year'].min(),

% max=df['year'].max(),

% value=df['year'].min(),

% marks={str(year): str(year) for year in df['year'].unique()},

% step=None

% )

% ] )

%

% @app.callback(

% [ Output('graph-with-slider', 'figure') ],

% [ Input('year-slider', 'value') ],

% )

% def update_figure( year ):

% filtered_df = df[ df.year==year ]

%

% fig = px.scatter(

% filtered_df,

% x='gdpPercap',

% y='lifeExp',

% size='pop',

% color='continent',

% hover_name='country',

% log_x=True,

% size_max=55

% )

%

% fig.update_layout( transition_duration=500 )

% return [ fig ]

%

% app.run_server(debug=True)

A Dash scatterplot showing GDP per capita versus life expectancy,

categorized by continent. The slider allows users to change the year

being visualized from 1952 to 2007

A Dash scatterplot showing GDP per capita versus life expectancy,

categorized by continent. The slider allows users to change the year

being visualized from 1952 to 2007

Of course, most dashboards will have multiple inputs and

outputs. How is this handled in Dash? For inputs, notice that

Input is embedded within a list. You can define multiple

Input statements in this list. For each

Input statement you add, another input argument is

included in your callback function.

% from dash import Dash

% from dash import html

% from dash import dcc

% from dash import Input

% from dash import Output

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% ext_SS = ['https://codepen.io/chriddyp/pen/bWLwgP.css']

% app = Dash(__name__, external_stylesheets=ext_SS)

%

% df = pd.read_csv( 'https://plotly.github.io/datasets/country_indicators.csv' )

%

% indicators = df[ 'Indicator Name' ].unique()

%

% app.layout = html.Div( [

% html.Div( [

% html.Div( [

% dcc.Dropdown(

% id='xaxis-column',

% options=[{'label': i, 'value': i} for i in indicators],

% value='Fertility rate, total (births per woman)'

% ),

% dcc.RadioItems(

% id='xaxis-type',

% options=[{'label': i, 'value': i} for i in ['Linear','Log']],

% value='Linear',

% labelStyle={'display': 'inline-block'}

% )

% ],

% style={'width': '48%', 'display': 'inline-block'}),

%

% html.Div( [

% dcc.Dropdown(

% id='yaxis-column',

% options=[{'label': i, 'value': i} for i in indicators],

% value='Life expectancy at birth, total (years)'

% ),

% dcc.RadioItems(

% id='yaxis-type',

% options=[{'label': i, 'value': i} for i in ['Linear','Log']],

% value='Linear',

% labelStyle={'display': 'inline-block'}

% )

% ],

% style={'width': '48%', 'float': 'right', 'display': 'inline-block'}),

% ] ),

%

% dcc.Graph( id='indicator-graph' ),

%

% dcc.Slider(

% id='year-slider',

% min=df['Year'].min(),

% max=df['Year'].max(),

% value=df['Year'].max(),

% marks={str(year): str(year) for year in df['Year'].unique()},

% step=None

% )

% ] )

%

% @app.callback(

% [ Output('indicator-graph', 'figure') ],

% [ Input('xaxis-column', 'value'),

% Input('yaxis-column', 'value'),

% Input('xaxis-type', 'value'),

% Input('yaxis-type', 'value'),

% Input('year-slider', 'value') ]

% )

% def update_graph( xaxis_col_nm, yaxis_col_nm, xaxis_type, yaxis_type, year ):

% dff = df[ df['Year']==year ]

%

% fig = px.scatter(

% x=dff[dff['Indicator Name']==xaxis_col_nm]['Value'],

% y=dff[dff['Indicator Name']==yaxis_col_nm]['Value'],

% hover_name=dff[dff['Indicator Name']==yaxis_col_nm]['Country Name'],

% )

%

% fig.update_layout(margin={'l': 40, 'b': 40, 't': 10, 'r': 0}, hovermode='closest')

% fig.update_xaxes(title=xaxis_col_nm, type='linear' if xaxis_type=='Linear' else 'log')

% fig.update_yaxes(title=yaxis_col_nm, type='linear' if yaxis_type=='Linear' else 'log')

% return [ fig ]

%

% app.run_server(debug=True)

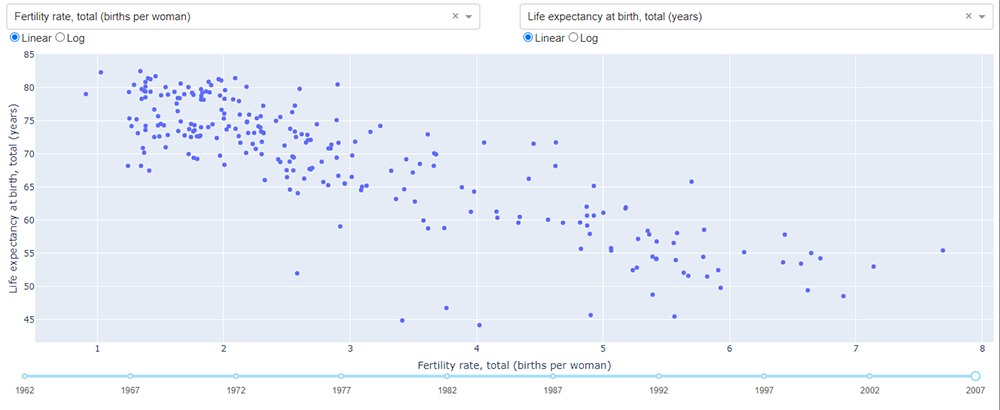

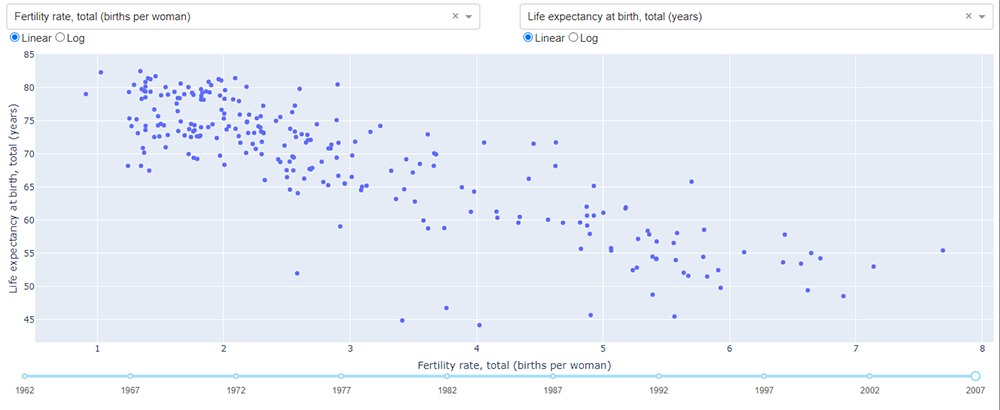

A Dash scatterplot with variable x and y-axes, as well

as the ability to display linear or logarithmic axis spacing, and to

choose the year of data to plot

A Dash scatterplot with variable x and y-axes, as well

as the ability to display linear or logarithmic axis spacing, and to

choose the year of data to plot

In this example, there are five input widgets: two dropdown menus,

two radiobutton groups, and a slider. All five are included in the

Input list: xaxis-column,

yaxis-column, xaxis-type,

yaxis-type, and year-slider,

respectively. In the update_graph function the values for

those five widgets are passed as xaxis_col_nm,

yaxis_col_nm, xaxis_type,

yaxis_type, and year. Other than this, the

function operates identically, returning an updated scatterplot based

on the five selected inputs.

Multiple outputs work in a similar way. First, you specify each

output as part of the list of Output statements. Then,

specify each output element in order in the list returned by the

callback function.

% from dash import Dash

% from dash import html

% from dash import dcc

% from dash import Input

% from dash import Output

% import plotly.express as px

% import pandas as pd

%

% ext_SS = ['https://codepen.io/chriddyp/pen/bWLwgP.css']

% app = Dash(__name__, external_stylesheets=ext_SS)

%

% df = px.data.gapminder().query( 'year==2007' )

% continents = df[ 'continent' ].unique()

%

% app.layout = html.Div(

% children=[

% dcc.Dropdown(

% id='continent',

% options=[ { 'label': c, 'value': c } for c in continents ],

% value=continents[ 0 ]

% ),

%

% dcc.Graph( id='bar' ),

% dcc.Graph( id='map' )

% ] )

%

% @app.callback(

% [ Output('bar', 'figure'),

% Output('map', 'figure') ],

% [ Input('continent', 'value') ]

% )

% def update_bar_map( continent ):

% dff = df[ df['continent']==continent ]

%

% bar = px.bar( dff, x='country', y='gdpPercap' )

% map = px.treemap(

% dff,

% path=['country'],

% values='pop',

% color='gdpPercap',

% color_continuous_scale='RdBu'

% )

%

% return [ bar, map ]

%

% app.run_server(debug=True)

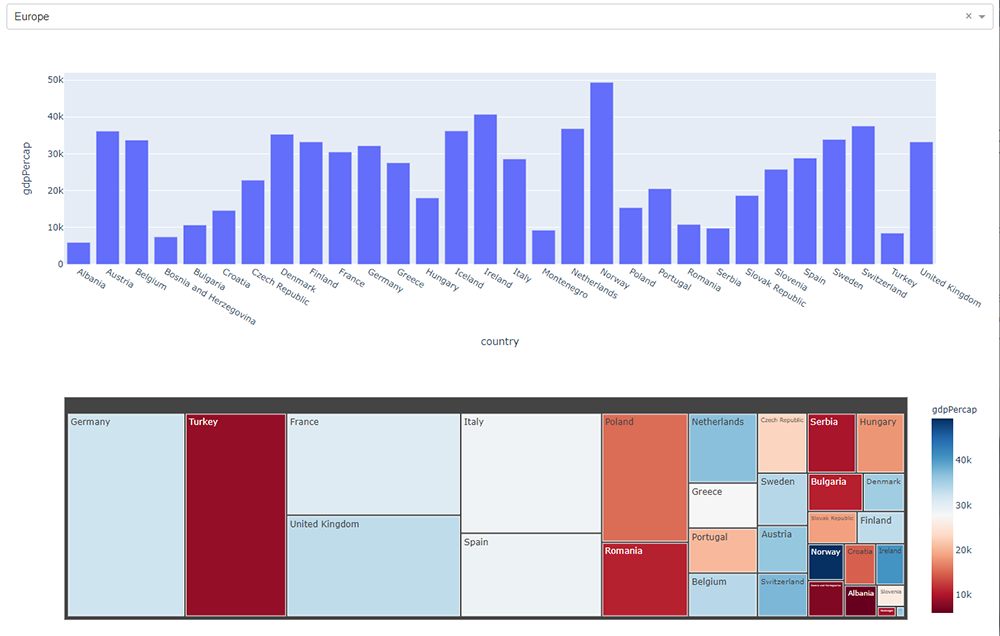

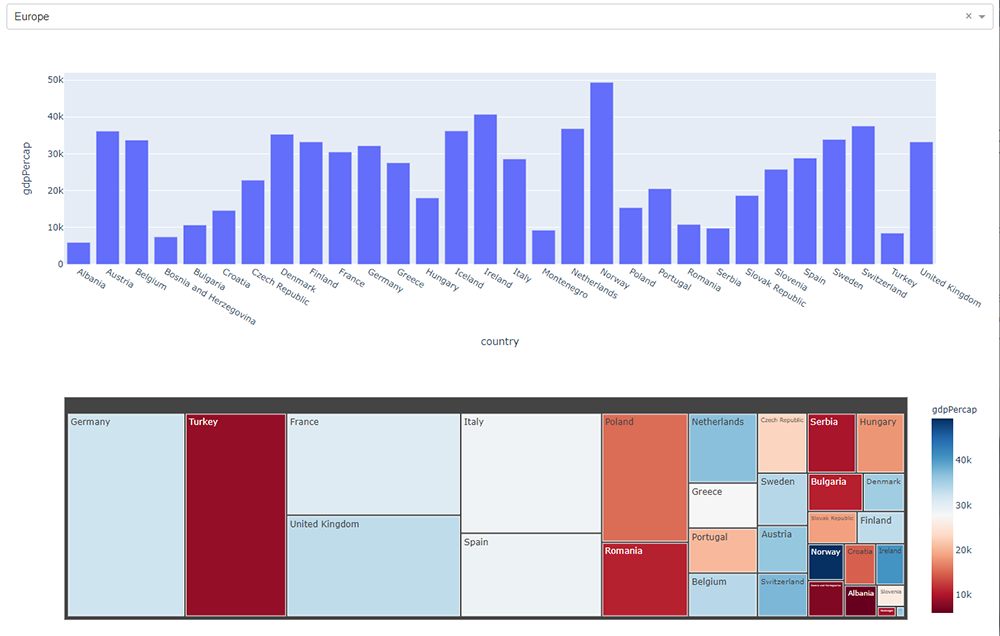

A Dash bar chart and treemap. The bar chart shows per capita GDP by country

for the user-chosen continent. The treemap show population by size and

per capita GDP by colour, by country for the user-chosen continent

A Dash bar chart and treemap. The bar chart shows per capita GDP by country

for the user-chosen continent. The treemap show population by size and

per capita GDP by colour, by country for the user-chosen continent

This dashboard shows the GDP per capita for countries in a

user-chosen continent. Continent selection is performed with a

standard dropdown menu. GDP per capita is shown in two

visualizations. The first uses a simple bar chart by country. The

second uses a treemap, where the size of the rectangle assigned to a

country represents its population, and the rectangle's colour

represents the GDP per capita from a red–blue double-ended

colour scale.

Publishing

Unfortunately, publishing a Dash dashboard is not as straight

forward as it is with other environments like R+Shiny. plotly does not

maintain a public cloud to upload dashboards. Various options are

suggested by different Dash users.

Dash itself suggests

the following documentation for deploying Dash

applications. Your milage may vary on this, but it is probably the

best starting point for attempt to build a Dash appliation that is

accessible from the web.